The Little Red Book

This little red book, like the Blue Scarf which I wrote about in an earlier blog, is special to our family. A tiny book – a reminder that my father, Steve McDougal and many thousands like him experienced what amounted to a war crime at the end of World War II: The March of 1945.

Zeigenhain, Germany, March 1945. Spring. Allied prisoners of war in Stalag IXA look across to the little village of Zeigenhain and see something they will never forget. White!! – flags, sheets, towels – hanging from the windows of houses, from buildings, from any object. White – the colour of surrender. It will be another five weeks before Germany officially surrenders but for these men, some of whom have been in captivity for four years or more, the war is over.

The prisoners notice the guards have left their posts. Before long four huge American tanks arrive one of which will crash through the prison camp gate in a dramatic act of symbolism. The Americans offer the prisoners reassurance and salt, the taste and restorative value of which my father will recall many times in the years to come. A medical team is sent in and, with what might be considered perfect timing, Steve McDougal blacks out.

Lamsdorf, German occupied Poland, 10 weeks earlier – Winter – one of the coldest on record The prisoners of Stalag 344 are ordered out of the camp. Where they are going and why, they are not told. Prisoners of war throughout Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia are similarly on the road. The Germans are moving them away from the advancing Russian Army and freedom. They are prolonging the war for these prisoners many of whom will die. All of them will suffer. Tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of prisoners interred in the camps will find themselves on a forced march in the early part of 1945 which became known variously as The Long March, The Long March West, The Long Trek or simply The March1.

My father’s group of about 1,500 head off down Chestnut Alley leaving the ‘hell hole’ Stalag 344 behind. They march on into the night and are up and on the road again early the next morning. Occasionally they march until midnight. They sleep in barns, churches, factories, military buildings. Temperatures drop to below -25oC that winter so a hay filled barn feels relatively warm. The factories and military buildings do not. They have concrete floors over which a layer of ice settles. When the men lay down the ice quickly turns into water. Many will not survive the night.

They march through blizzards, snow swirling and howling around them and visibility reduced to zero. On sunny days the snow is blinding. Men wrap anything they can find around their eyes to protect them from the glare and some are led by their mates. Steve McDougal believes the colour red will help and trudges hour upon hour staring transfixed at the red pannikin tied to the haversack of his mate walking in front.

On they go, day after day2. The pace slows. They are already weak from the years of imprisonment and the meagre camp rations. The Red Cross supplies they brought from the camp are soon gone. They survive on potatoes, watery cabbage soup and bread. Some days there is no food. They lose weight. They are forced to scavenge. They take risks. Steve McDougal sneaks through an open door of a cottage and grabs potatoes from the stove of a startled German family. His good friend Wally Walsh sells his treasured watch to a civilian for ½ loaf black bread and a few potatoes.

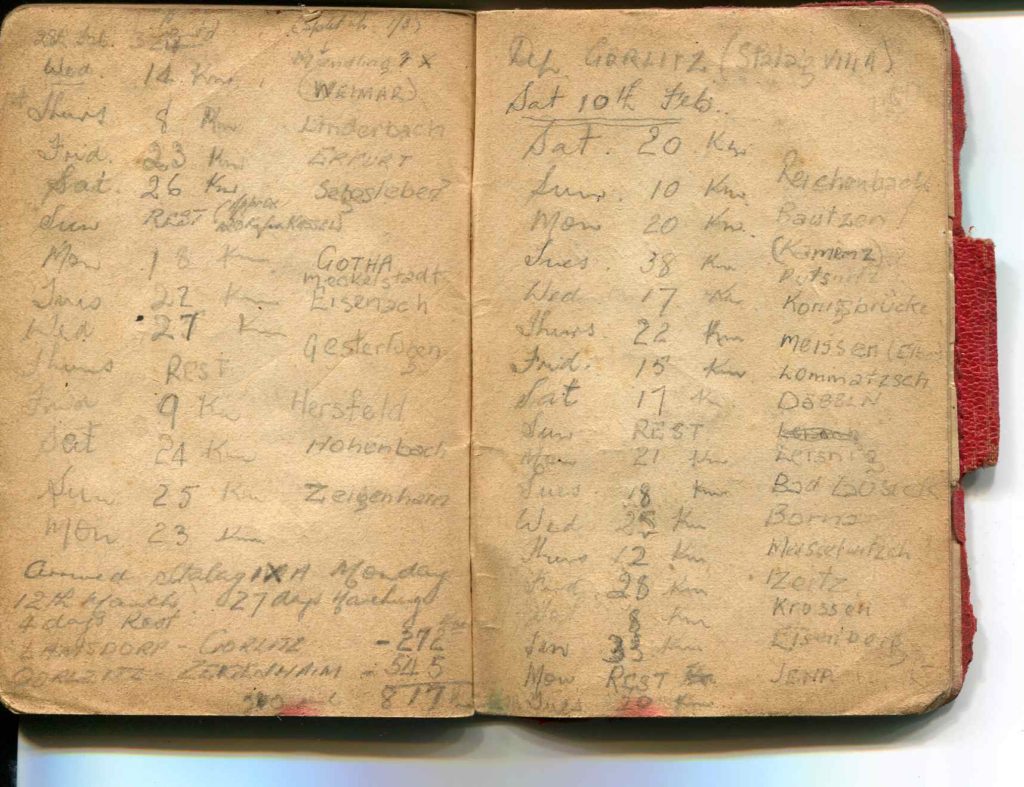

Each day my father notes down the direct distances as shown on the road signposts. Nineteen kilometres a day is the average marched. At the bottom the page in his little red book a tally – Lamsdorf to Gorlitz 272kms, Gorlitz to Zeigenhain 545kms- total 817kms3.

But the distance was much more than that. Not counted were the kilometres walked from the track to each night’s shelter. Nor was it possible to estimate distances when the prisoners were marched in circles. Steve McDougal kept up morale by imagining he was slowly advancing towards ‘his own people’. How dispiriting to realise his group had marched all day only to return to the same spot. Other groups report the same problem, some report marching 1,000kms, others 1,500kms.

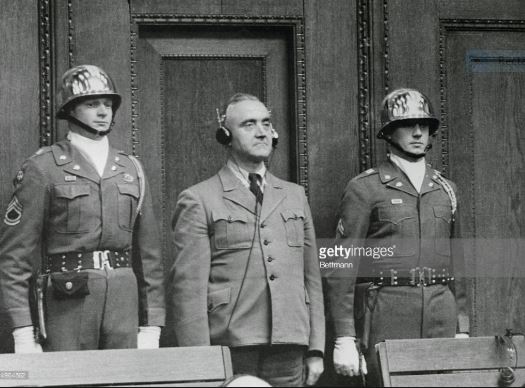

Nuremberg, Germany 1949. SS Generalleutnant Gottlob Berger who oversaw the POW camps in 1944 stands trial for the treatment of prisoners on the Long March. The indictment is read out:

that between September 1944 and May 1945, hundreds of thousands of American and Allied prisoners of war were compelled to undertake forced marches in severe weather without adequate rest, shelter, food, clothing and medical supplies; and that such forced marches, conducted under the authority of the defendant Berger, chief of Prisoner-of-War Affairs, resulted in great privation and deaths to many thousands of prisoners.[4]

Berger argues that he had a duty according to the Geneva convention of 1929 to remove the prisoners from the area of combat, that he had protested Hitler’s decision but could not disobey orders. Though later convicted for the genocide of European Jews when he will serve six of his 25-year sentence, this time there is no guilty verdict. He walks free. His arguments prevailed and there are few eyewitness accounts. Most ex-POWs are unaware that the trial has taken place.

At the time Steve McDougal is living in Haberfield with his wife Thelma and two-year old me. His little red book is now filled with the minutiae of civilian life – items of furniture for the home of a newly married man, lists of books to read, addresses and phone numbers, a note to phone an aunt.

If he ever knew or cared about the fate of Gottlob Berger he never said. He wrote about his experience of The March with candour and without rancour. When he related the story, it was the positives he emphasised; the mateship, the look on the faces of the German family as he grabbed their potatoes, the wonderful taste of salt on the day of liberation.

Note: Steve McDougal was hospitalised in Frankfurt-au-Main, Wales, then England. He returned to Australia in June 1945.

Footnotes

- Estimates vary: one gives the numbers as approx. 960,000 in three main groups – the northern line – approx. 100,000 prisoners, the central line – approx. 60,000 and the southern line – approx. 800,000 many of whom were Russian, the latter with a small percentage Allied prisoners but still estimated to be tens of thousands, pp.170-72 Nichol J and Rennel T. The Last Escape: The Untold Story of Allied Prisoners of War in Europe 1944-45; Viking, 2003.

Wikipedia estimates that of the 257,000 Allied prisoners of war about 80,000 were forced out of the camps and to march, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_March_(1945)

- Forty-nine days on the road; forty days marching with nine days rest.

- RAF Bomber Command navigator, Jim Badcock presumably marched the same distance as Steve McDougal as he was on the road for the same amount of time and arrived at Stalag IXA, the Zeigenhaim camp on the same day. He estimated the distance as 600 miles which is just under 967kms.

- Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law, No. 10, Vol VIII (Washington, D.C: US Government Printing Office, 1962 in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_March_(1945)

The story above taken from Steve McDougal’s own account from his undated and unpublished article: The Long Trek.

‘The March’ has been largely left out of post war history as the holocaust and the Burma Railway atrocities took precedence. But the few bullet points below, taken from John Nichols and Tony Rennell’s book (see ref above) incorporating the history and accounts of those on the March, give an idea of an event that should never be forgotten.

- The movement of prisoners away from the Russians who could have liberated them was unnecessary and avoidable and amounted to an atrocity of war. No arrangements were made to feed and shelter the prisoners and they were marched harder and father than allowed by the Geneva Convention.p.164

- Some prisoners were on the road for weeks before the world knew. There was no way they could communicate to the outside world of their plight. Authorities in Britain and the US were slow to act assuming that Germany would surrender in an orderly manner and that prisoners of war would remain in the camp and wait for their liberators. p.166

- Some groups were forced to sleep in the open in the coldest winter months reported in the 20th century. pp.135-7.

- Thousands of prisoners suffered from illness such as dysentery, typhus, malaria, pneumonia, malnutrition, exposure, tuberculosis, trench foot, some walked the whole way in clogs, some had frostbite severe enough to advance to gangrene. Many died of disease, exhaustion, starvation and medics had virtually no medicines or equipment with which to treat the sick. pp.149-50, 178-9.

- Most were in a weakened state before the march from years of inadequate camp food. By the time they were liberated many were half their pre-war weight, Wikipedia ref above.

- 30 British prisoners died with another 30 probably fatally wounded at Gresse when they were strafed by ‘friendly fire’- RAF Typhoons.pp.329-47.

- Conflicting evidence as to why prisoners moved. Some justification for removing prisoners from battle zones initially but the Allies lifted this requirement and it was ignored. Instead prisoners were at risk of strafing from aircraft from both sides (see RAF Typhoons above).

- Possible motives were that the prisoners were to be used as hostages, as leverage for peace agreement or to prolong the war.pp199, 445-6

- Hitler had ordered the removal of prisoners from the camps as early as July 1944 which makes the motives difficult to analyse. Probably a number of reasons and decisions were often made by German officers to move prisoners and themselves away from the feared SS troops. pp.109-13, 445-6

- Berger was released from prison early in 1951– serving just 6 of his 25-year sentence. The court maintained that he saved the lives of many prisoners because he consistently disobeyed orders: he did not cut down food supplies to the camps, nor halt Red Cross supplies, did not send hard line SS officers into the camps to replace military guards, did not shoot VIP prisoners but guided them to safety and generally did not crack down hard on prisoners. He spent the rest of his life in the US associating with POW groups and generally building up his reputation as a good German pp.357-69.

- The numbers who died on the marches vary, An estimate from the US Veterans Affairs gives the number at 3,500 while Chris Christiansen, a Danish aid worker working for the YMCA in the camps at the time estimates the numbers of Commonwealth and US deaths to be as high as 8,348 .p.447 Nichol et al and reference 2 wikepedia above – Seven Years Amongst Prisoners of War.

Photo attributions:

Chestnut Alley – from a story published in the Weekend Australian, 21-22 April, 2018 by Lee Mylne, My Father Was Here.

Gottlob Berger – By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S73321 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5665928

Zeigenhain Village – Alamy Stock Photos

D5 Creation

D5 Creation

I have recently started a site, the info you offer on this web site has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Along with everything which seems to be building inside this specific subject material, your perspectives are generally quite exciting. However, I appologize, because I can not subscribe to your entire strategy, all be it radical none the less. It looks to everybody that your remarks are actually not totally validated and in actuality you are generally yourself not really fully certain of your assertion. In any event I did enjoy reading it.