Author: Jeanette

The Little Red Book

This little red book, like the Blue Scarf which I wrote about in an earlier blog, is special to our family. A tiny book – a reminder that my father, Steve McDougal and many thousands like him experienced what amounted to a war crime at the end of World War II: The March of 1945.

Zeigenhain, Germany, March 1945. Spring. Allied prisoners of war in Stalag IXA look across to the little village of Zeigenhain and see something they will never forget. White!! – flags, sheets, towels – hanging from the windows of houses, from buildings, from any object. White – the colour of surrender. It will be another five weeks before Germany officially surrenders but for these men, some of whom have been in captivity for four years or more, the war is over.

The prisoners notice the guards have left their posts. Before long four huge American tanks arrive one of which will crash through the prison camp gate in a dramatic act of symbolism. The Americans offer the prisoners reassurance and salt, the taste and restorative value of which my father will recall many times in the years to come. A medical team is sent in and, with what might be considered perfect timing, Steve McDougal blacks out.

Lamsdorf, German occupied Poland, 10 weeks earlier – Winter – one of the coldest on record The prisoners of Stalag 344 are ordered out of the camp. Where they are going and why, they are not told. Prisoners of war throughout Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia are similarly on the road. The Germans are moving them away from the advancing Russian Army and freedom. They are prolonging the war for these prisoners many of whom will die. All of them will suffer. Tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of prisoners interred in the camps will find themselves on a forced march in the early part of 1945 which became known variously as The Long March, The Long March West, The Long Trek or simply The March1.

My father’s group of about 1,500 head off down Chestnut Alley leaving the ‘hell hole’ Stalag 344 behind. They march on into the night and are up and on the road again early the next morning. Occasionally they march until midnight. They sleep in barns, churches, factories, military buildings. Temperatures drop to below -25oC that winter so a hay filled barn feels relatively warm. The factories and military buildings do not. They have concrete floors over which a layer of ice settles. When the men lay down the ice quickly turns into water. Many will not survive the night.

They march through blizzards, snow swirling and howling around them and visibility reduced to zero. On sunny days the snow is blinding. Men wrap anything they can find around their eyes to protect them from the glare and some are led by their mates. Steve McDougal believes the colour red will help and trudges hour upon hour staring transfixed at the red pannikin tied to the haversack of his mate walking in front.

On they go, day after day2. The pace slows. They are already weak from the years of imprisonment and the meagre camp rations. The Red Cross supplies they brought from the camp are soon gone. They survive on potatoes, watery cabbage soup and bread. Some days there is no food. They lose weight. They are forced to scavenge. They take risks. Steve McDougal sneaks through an open door of a cottage and grabs potatoes from the stove of a startled German family. His good friend Wally Walsh sells his treasured watch to a civilian for ½ loaf black bread and a few potatoes.

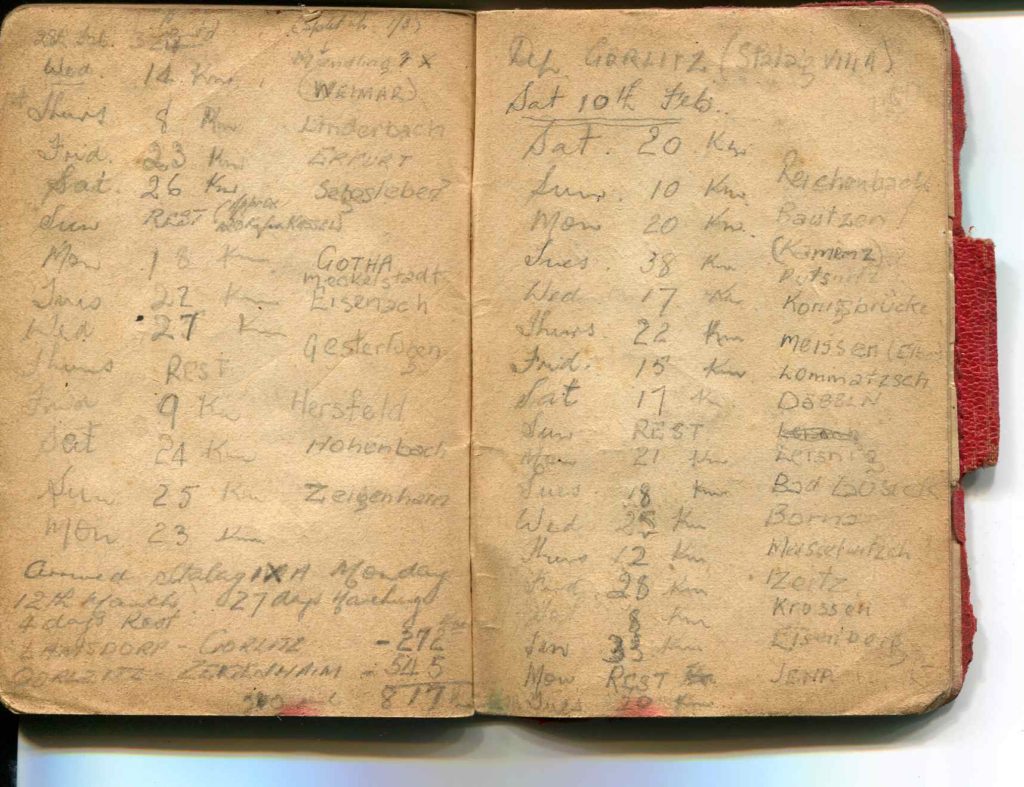

Each day my father notes down the direct distances as shown on the road signposts. Nineteen kilometres a day is the average marched. At the bottom the page in his little red book a tally – Lamsdorf to Gorlitz 272kms, Gorlitz to Zeigenhain 545kms- total 817kms3.

But the distance was much more than that. Not counted were the kilometres walked from the track to each night’s shelter. Nor was it possible to estimate distances when the prisoners were marched in circles. Steve McDougal kept up morale by imagining he was slowly advancing towards ‘his own people’. How dispiriting to realise his group had marched all day only to return to the same spot. Other groups report the same problem, some report marching 1,000kms, others 1,500kms.

Nuremberg, Germany 1949. SS Generalleutnant Gottlob Berger who oversaw the POW camps in 1944 stands trial for the treatment of prisoners on the Long March. The indictment is read out:

that between September 1944 and May 1945, hundreds of thousands of American and Allied prisoners of war were compelled to undertake forced marches in severe weather without adequate rest, shelter, food, clothing and medical supplies; and that such forced marches, conducted under the authority of the defendant Berger, chief of Prisoner-of-War Affairs, resulted in great privation and deaths to many thousands of prisoners.[4]

Berger argues that he had a duty according to the Geneva convention of 1929 to remove the prisoners from the area of combat, that he had protested Hitler’s decision but could not disobey orders. Though later convicted for the genocide of European Jews when he will serve six of his 25-year sentence, this time there is no guilty verdict. He walks free. His arguments prevailed and there are few eyewitness accounts. Most ex-POWs are unaware that the trial has taken place.

At the time Steve McDougal is living in Haberfield with his wife Thelma and two-year old me. His little red book is now filled with the minutiae of civilian life – items of furniture for the home of a newly married man, lists of books to read, addresses and phone numbers, a note to phone an aunt.

If he ever knew or cared about the fate of Gottlob Berger he never said. He wrote about his experience of The March with candour and without rancour. When he related the story, it was the positives he emphasised; the mateship, the look on the faces of the German family as he grabbed their potatoes, the wonderful taste of salt on the day of liberation.

Note: Steve McDougal was hospitalised in Frankfurt-au-Main, Wales, then England. He returned to Australia in June 1945.

Footnotes

- Estimates vary: one gives the numbers as approx. 960,000 in three main groups – the northern line – approx. 100,000 prisoners, the central line – approx. 60,000 and the southern line – approx. 800,000 many of whom were Russian, the latter with a small percentage Allied prisoners but still estimated to be tens of thousands, pp.170-72 Nichol J and Rennel T. The Last Escape: The Untold Story of Allied Prisoners of War in Europe 1944-45; Viking, 2003.

Wikipedia estimates that of the 257,000 Allied prisoners of war about 80,000 were forced out of the camps and to march, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_March_(1945)

- Forty-nine days on the road; forty days marching with nine days rest.

- RAF Bomber Command navigator, Jim Badcock presumably marched the same distance as Steve McDougal as he was on the road for the same amount of time and arrived at Stalag IXA, the Zeigenhaim camp on the same day. He estimated the distance as 600 miles which is just under 967kms.

- Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law, No. 10, Vol VIII (Washington, D.C: US Government Printing Office, 1962 in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_March_(1945)

The story above taken from Steve McDougal’s own account from his undated and unpublished article: The Long Trek.

‘The March’ has been largely left out of post war history as the holocaust and the Burma Railway atrocities took precedence. But the few bullet points below, taken from John Nichols and Tony Rennell’s book (see ref above) incorporating the history and accounts of those on the March, give an idea of an event that should never be forgotten.

- The movement of prisoners away from the Russians who could have liberated them was unnecessary and avoidable and amounted to an atrocity of war. No arrangements were made to feed and shelter the prisoners and they were marched harder and father than allowed by the Geneva Convention.p.164

- Some prisoners were on the road for weeks before the world knew. There was no way they could communicate to the outside world of their plight. Authorities in Britain and the US were slow to act assuming that Germany would surrender in an orderly manner and that prisoners of war would remain in the camp and wait for their liberators. p.166

- Some groups were forced to sleep in the open in the coldest winter months reported in the 20th century. pp.135-7.

- Thousands of prisoners suffered from illness such as dysentery, typhus, malaria, pneumonia, malnutrition, exposure, tuberculosis, trench foot, some walked the whole way in clogs, some had frostbite severe enough to advance to gangrene. Many died of disease, exhaustion, starvation and medics had virtually no medicines or equipment with which to treat the sick. pp.149-50, 178-9.

- Most were in a weakened state before the march from years of inadequate camp food. By the time they were liberated many were half their pre-war weight, Wikipedia ref above.

- 30 British prisoners died with another 30 probably fatally wounded at Gresse when they were strafed by ‘friendly fire’- RAF Typhoons.pp.329-47.

- Conflicting evidence as to why prisoners moved. Some justification for removing prisoners from battle zones initially but the Allies lifted this requirement and it was ignored. Instead prisoners were at risk of strafing from aircraft from both sides (see RAF Typhoons above).

- Possible motives were that the prisoners were to be used as hostages, as leverage for peace agreement or to prolong the war.pp199, 445-6

- Hitler had ordered the removal of prisoners from the camps as early as July 1944 which makes the motives difficult to analyse. Probably a number of reasons and decisions were often made by German officers to move prisoners and themselves away from the feared SS troops. pp.109-13, 445-6

- Berger was released from prison early in 1951– serving just 6 of his 25-year sentence. The court maintained that he saved the lives of many prisoners because he consistently disobeyed orders: he did not cut down food supplies to the camps, nor halt Red Cross supplies, did not send hard line SS officers into the camps to replace military guards, did not shoot VIP prisoners but guided them to safety and generally did not crack down hard on prisoners. He spent the rest of his life in the US associating with POW groups and generally building up his reputation as a good German pp.357-69.

- The numbers who died on the marches vary, An estimate from the US Veterans Affairs gives the number at 3,500 while Chris Christiansen, a Danish aid worker working for the YMCA in the camps at the time estimates the numbers of Commonwealth and US deaths to be as high as 8,348 .p.447 Nichol et al and reference 2 wikepedia above – Seven Years Amongst Prisoners of War.

Photo attributions:

Chestnut Alley – from a story published in the Weekend Australian, 21-22 April, 2018 by Lee Mylne, My Father Was Here.

Gottlob Berger – By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S73321 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5665928

Zeigenhain Village – Alamy Stock Photos

Stuff you might need to escape a POW camp – Part I

British, NZ & Aust POWs arrive from Crete & Salonika, 1941

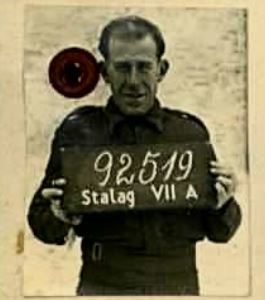

Stalag VIIA in Moosburg Germany was set up initially for French prisoners of war. After their forced surrender at the Battle of Crete in 1941 my father, Steve McDougal and some of the soldiers of his army unit, the 2/3rd Field Regiment found themselves at Stalag VIIA and then at Westend Labour Camp, Munich.

Stalag VIIA Sign – Prisoner of War Camp – Enlisted Men’s Camp

My last blog told of Steve McDougal’s escape attempt from the labour camp.

He wasn’t the only one with escape on his mind!

Escape is the dream, the obligation, the driving force of so many who find themselves in a POW camp. But how to get out? If the camp has a thriving black market of the type that operated in Stalag VIIA then maybe, just maybe, one might find an item that could be used. Then, all that is needed is something to exchange for the item and lots of imagination and daring. And of course, luck!

A humble tape measure might be easily overlooked as a way to quit the camp. But two French prisoners simply asked the guard at the gate to let them through as they had to survey the road. They held their nerve and ‘measured’ their way down the road, our of sight and were never seen again!

Stalag VIIA Entrance

A ladder might seem obvious but if it was carried through the gate with confidence, then who knows how far two men might go? In this case about 10kms from the border before two men were questioned and returned to camp.

French POW still in women’s clothes after his failed escape attempt

Also out of luck and sent back to camp were two prisoners dressed as women. In their case women’s clothing and a bicycle was all it took for the two prisoners to cycle their way as far as Yugoslavia before they too were caught. They were returned to camp still in their women’s garb but with a healthy growth of facial hair!

Would twine be useful? An Australian and a Welshman thought so. Over many months they collected lots of it, wove it carefully into a hammock. Then, on the allotted day, one of them wound the hammock around his waist and under his great coat. The two men slipped away from a working party, then crawled along the nearby railway track to the station where a train headed for Switzerland was about to leave. Slinging the hammock beneath the train with barely enough time to get into it as the train started up, the two men lay in their cocoon, hardly daring to move in case they were tipped out. Hour after hour they suffered the cold and the stones, mud and debris that were thrown up at them. Worse than that though was the tension they felt as the train was searched at each station but especially at the border where the Gestapo was particularly thorough. Searching slowly through the interior including the engine and guard van, the guards then shone their torchlight under the train, starting at the rear and making their way slowly but inevitably towards the two men who were now resigned to their fate….except, that suddenly the train lurched forward and with it the men’s relief and realisation that they really were going to make it as the train sped on into Switzerland and freedom.

St Margrathen Railway Station, Swiss Border

But a map – that’s the thing that was always uppermost in the minds of those who were set on escape. My next blog tells the story of how Steve McDougal, whilst in Stalag VIIA and then Westend Labour Camp, managed to gather together his precious items for his escape attempt .

Stuff you might need to escape a POW camp – Part II

The story continues of my father, Steve McDougal and his escape and eventual capture from a German Prisoner of War Labour Camp.

A map – that most sought after and hard to come by item – so essential for escape. Steve McDougal managed to get hold of two! The first, acquired in Stalag VIIA from a French prisoner was a very small yet detailed sketch of the German frontier in the area west of the Austrian town Bludenz. On the back of the map the man included detailed instructions. The other, which came from a street sweeping party near the Westend camp, was a military map for which my father paid a high price in tea, chocolates, soap and cigarettes.

Now, with two maps my father’s escape seemed feasible. All he had to do was collect and hide food and steal clothing so that he could pass himself off as a civilian worker. But hiding things was not easy. The barracks were often searched to discourage hoarding which was a sure sign of an escape attempt. The POWs often returned from a hard day’s work to find their barracks turned upside down. This was always unpleasant but there was a worse deterrent for would-be escapees. The prisoners presented their food bowls with their Red Cross food parcels, then were ordered to open each can of food and tip it in. In went the packet of tea, then cocoa,

Stalag VIIA Meal Distribution

pieces of chocolate, perhaps soap, then biscuits, sardines or herrings with condensed milk poured over the top! Fortunately for the prisoners, the Germans did not persist with this sadistic game.

But Steve McDougal managed to collect tins of bully beef, chocolate, raisins, army biscuits and hid them around the yard ‘like a dog’. From civilian workers he swapped tea and soap for a water bottle and ‘meta’ tablets which he would use as fuel. An empty tin of powdered milk filled with water and bonox cubes could be heated with the tablets and make a satisfying, hot drink.

Now the final decision – to go with a mate or to go alone. He had friends who had escaped in twos or threes only to get as far as nearby Munich because of the mistake or carelessness of one. And so, he decided to go alone.

At a final briefing from the padre and doctor this is what he was told: all decisions would be his and he would stand or fall by them. With no-one to talk things over loneliness would be his constant companion. In the hostile environment out there no person could be trusted. He was told to double and treble his precautions as he neared the border. By then his nerves would be on edge and he probably would not have eaten over much. If, in the unfortunate situation he was caught on no account was he to give up his identity tags, his most valuable link. As he would be in civilian clothing he would almost certainly be labelled a saboteur and therefore not under the protection of the Red Cross. How prophetic these words!

And so, Steve McDougal was caught at the border and was accused of being a spy and a saboteur. His interrogator argued he could not be a POW not only because of his clothing but also because no British or Australian soldier had been caught in the area before. He had taped the sketch of the border area to the underside of his left foot. The map, if found would further incriminate him. But it was not found. He was interrogated ‘naked and shivering’ . Why was the map not found? Because the guards did not look under his left foot but under his right foot – twice!

Forty-four years later my father wrote of his escape attempt and was able to recall, no doubt with word-perfect accuracy, those instructions hidden under his foot and which were given to him by the Frenchman in Stalag VIIA:

‘Leave Bludenz between 3.30 – 4.00am. Seek out the main Autobahn which is adjacent to and on the left of the railway line. Follow the Autobahn which runs in a north-westerly direction for 6.5 kilometres until sighting four small farm buildings. A secondary road branches off to the south (left) at this point. This is just prior to the Autobahn crossing – a swift stream by means of a small bridge. Follow this secondary road. It will gently climb and then pass through a small village. It is the main and only street in the village. After passing through the village the road dwindles to a cart track. The stream will be on your right hand side. The cart track will continue to rise in a west-south-westerly direction. Eventually the cart track will become just a foot track. You will climb very steeply with the river far below. Take particular care as landslides could have cut the track or, if on the wrong track, it is possible to walk over the edge. You should be in the area in the dark of the morning. Stop well before coming to the actual frontier, which will be easily identifiable. Observe the frontier posts all through the day. Cross at the point where indicated but not before 8.00pm. Take extreme care even when over the frontier for if observed a frontier patrol will try to bring you back. They could succeed. Or they will shoot you. Use the edge of the glacier which is part in Liechtenstein and make your way to Switzerland. Aim to cross the frontier mid to late November. The patrols are weakened for the winter and if possible before the heavy falls of snow’.

And now, here I am 76 years later looking at a map where I can see the railway line and  the autobahn running west of Bludenz. Not a paper map of the type that could be folded to fit into a pocket or a tiny 4×6 inch sketch that could be hidden under a foot but one devised by technology – Google Earth.

the autobahn running west of Bludenz. Not a paper map of the type that could be folded to fit into a pocket or a tiny 4×6 inch sketch that could be hidden under a foot but one devised by technology – Google Earth.

As I zoom in I wonder, could Brand village be the village through which my father crawled along the narrow cobblestone street at 4am, his boots ‘high from the ground’ so as not to wake the domestic dogs? And might that be the church where the border patrol took him and placed him in a cell? And will Google Earth allow me a street-view, so I can take a virtual walk through this village? No as it turns out but one day I hope the technology will let me take that walk.

Brand Village, Austria

And wouldn’t my father be amazed to see me sitting at my computer pondering such an idea? But that’s the magic of maps.

Finally, how did my father make his escape? He put the stolen jacket on under his great coat in whose pockets he had put the scarf, cap and some food. His working party travelled a short distance to their daily place of work as fettlers in a railway yard. When they arrived at the work hut the men placed their midday meal of soup on the large table, removed tools from a long wooden box and my father got into it. One of the guards came in, glanced around to see if all was in order and then the party moved off. Stuffing all the things from the pockets of the great coat into his rucksack and pockets of the jacket, my father tossed the great coat into the box and made for the door. No-one around so he slipped along the side of the hut, gathered up the rest of the stashed food then made his way to a nearby stone quarry where he spent the day overlooking the hut until the working party left in the evening. By then his absence had been noted but he was safe and once he left that quarry he could pass himself off, if not as a German worker, then at least a foreign civilian worker and in this disguise and with his precious maps, made his way through Germany to Austria and the Swiss border.

References:

McDougal, Stephen Walter, Grab for Freedom, Good Weekend, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 August 1989.

McDougal, SW, Untitled, unfinished and unpublished article. June-July 1986.

Thomas, Vince in: The Unofficial History of the 2/3rd Field Regiment, Lind, Lew (ed), Chapter XIV 1976, pp22-25.

Wilson, Rupert in: The Unofficial History of the 2/3rd Field Regiment, Lind L (ed), Chapter XIV 1976, p.21.

Photos – from Moosburg online – www.moosburg.org and the Australian War Memorial website – https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/complex-story-australian-prisoners-war. Brand village from https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/brand-bludenz-vorarlberg-austria-april-30-635136956

Welcome to my Blog – Family Stuff

Welcome and thanks for dropping by. My name is Jeanette Vizzard and this is my first blog!

I want to get my family stuff, the family stories ‘out there’ – into the blogosphere, into cyberspace or wherever you might be.

The ‘stuff’ might be stories I have been told, have researched or stories about stuff we have around the house like the blue scarf I’m going to tell you about today.

2 family members – Buffy and Clive

The story is about my father, Stephen Walter McDougal who served in the 2/3rd Field Regiment in World War II and who became a prisoner of war after capture on Crete – and about the significance of a blue scarf in his ‘grab for freedom’ from prisoner of war camp Stalag VIIA.

Here are the first few lines – keep reading by going to the next post for the whole story. Hope you enjoy it.

This blue scarf, a coat and a cap were hung on a peg one morning in a railway yard in Germany during World War II where Australian prisoners of war were working. The civilian worker who put them there went home cold that evening.

This blue scarf, a coat and a cap were stolen that day by my father.

This Blue Scarf

This blue scarf, a coat and a cap were hung on a peg one morning in a railway yard in Germany during World War II where Australian prisoners of war were working. The civilian worker who put them there went home cold that evening.

This blue scarf, a coat and a cap were stolen that day by my father.

Why? Because they would become part of a stash of items he needed for his escape. He had already buried chocolate, raisins and a can of bully beef. These items amongst others were going to sustain him in his ‘Grab for Freedom’ from a labour camp associated with the prisoner of war camp Stalag VIIA and the blue scarf, the coat and the cap would allow him to pass unnoticed through Germany and on to the Swiss border and freedom.

My father wrapped that blue scarf around his neck and made his escape. He hid in a stone quarry above the railway yard and when it was safe to do so, jumped on the back of a train. Later, he blackened his face and hid in a wagon load of potatoes.

His luck held when the train stopped right outside a civilian clocking-in station, the busiest part of the railway yard. How it was that no-one saw him scrambling out of that wagon seems inconceivable. Perhaps a foreign worker decided to keep quiet about it. Whatever the case, my father couldn’t believe his luck.

In the compartment on another train he was bullied by some drunks and when they got off, started talking to the ticket collector. My father expected to be dragged off the train at the next stop. But his luck held.

And again, when he was discovered alone on a stationery train at night. A shot was fired as he leapt from the train and ran, under stationary wagons, over railway lines, on through the railway yard and finally, lungs bursting with the exertion, into the safety of the forest.

His luck held when he decided to ride as a passenger on another train. A ticket collector came by and my father, head against the window, pretended to be asleep. ‘Sleeping, sleeping, people are always sleeping’ muttered the guard as he let me father be.

But my father’s luck ran out within sight of the border, just as he started to believe he was going to make it into Switzerland. Fearing crossing a creek at night in steep mountainous country he returned in the morning to find the creek presented no problem but around the next bend he encountered a German frontier guard and his snarling dog.

No use now, the blue scarf, the coat and the cap, in fact, they worked against my father. During a five-hour interrogation where he stood naked and shivering in a ‘cold cheerless room’ his interrogator, an Oxford-accented German SS officer accused him of being a civilian saboteur, a spy, and not an Australian soldier. After all, reasoned the officer he had been dressed as a civilian and been caught in an area where no Australian or British soldier had been caught before. The captain was not pleased, nor as he told my father was the Third Reich. So displeased was this officer, that at one stage my father thought he may be shot! Such was the tension in the room. But, of course he was able to produce his Army dog tags and his Prisoner of War disc.

But the charge of sabotage stuck, and it was now brought to light that my father had broken a large crate of glass whilst working as a railway goods porter and that he had been caught placing sand and loose nuts and bolts into the open-crated aeroplane engines. Time for punishment. He had already served time in solitary confinement in cold cells before being brought back to the camp and it was now decided he be sent off do hard labour at a stone quarry near Linz, but that is another story.

The blue scarf travelled with my father after he left the quarry to the next camp Stalag VIIIB, Lamsdorf and then on what is known as ‘The Long March’ – a forced march of prisoners of over 850kms at the end of the war and finally, to camp IXA at Ziegenhein. When the camp was liberated my father was sent to Wales and England to recuperate. Then home to Australia in June 1945, the blue scarf still with him.

As I write this, I can look across my living room and see that blue scarf in my glass-fronted bookcase. What a special piece of family stuff!

References

McDougal, Stephen Walter, Grab for Freedom, Good Weekend, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 August 1989.

McDougal, SW, ‘Rock City’; an experience, Blindheim, Germany Jan – Feb – Mar 1943. Unpublished article.

McDougal, SW, Untitled, unfinished and unpublished article. June-July 1986.

There is a lot on the web about Stalag VIIA – wikiepedia and moosburg online.

The Long March – Lamsdorf and The Long March to Freedom trailer – YouTube

D5 Creation

D5 Creation